Beyond the Stars: The U.S. Space and Rocket Center

The U.S. Space and Rocket Center is the largest spaceflight museum in the world.

Other landmarks like Mammoth Cave may not be apparent until you’re well within the bounds of the establishment, but here you know exactly what you’re getting into. This is on account of the massive Saturn V rocket towering over the Huntsville skyline as soon as you’re off the interstate. It’s a landmark of the city, reaching a full sixty feet taller than the Statue of Liberty, and certainly possessing more power. On launch it was said to generate 7.6 million pounds of thrust, consuming 1,500 gallons of fuel in the process. It’s hard to imagine being there, and perhaps even harder to picture the feeling of being inside the rocket itself.

But now it lies dormant. Nothing more than a husk of what it once was, it still showcases the undeniable sense of pride and nationalism you would expect from an American achievement. Perhaps this isn’t unjustified; being the first to put a man on the moon was no small feat.

The main entrance to the museum, marked by a military plane out front, leads directly into a large gift shop. From there, broad hallways lead to the main ticketing desk. The museum advertises general entry as well as set times for shows, which take place in what is known as the Planetarium theater. But for now, it was time to see the main exhibits.

To the right of the ticket desk, an opening becomes a futuristic hallway. Metal portholes with green and pink shapes of astronauts and spaceships adorn the walls. Around a corner is the first room of the museum proper, which largely focuses on the pop culture impact of the space race. Display cases of baubles and trinkets from the 60s and 70s dot the walls, along with advertisements of space missions made to look like movie posters. Above it all is a projector screen playing historical footage of engineers and officials discussing their plans. At the forefront of it all is Dr. Wernher von Braun, a prominent engineer in the development of moon landing technology. It’s a simple but effective display of what was at the forefront of every American’s mind some fifty years ago. Children move back and forth between the display cases and chatter excitedly; maybe the fascination never stopped after all.

That fascination was important to von Braun as well. He was obsessed with space travel in his formative years, likely no differently than many other children who have walked these halls. For his thirteenth birthday, his mother gave him a telescope which helped ignite this passion even further; one can imagine the young engineer gazing up at the stars, letting his mind run free of the world around him.

Beyond the first room is where the serious artifacts begin to appear. Turning the corner, the wall to the right holds a glass case with five space suits lined up for examination. The children from the previous room get really riled up here; one boy yells at the others to pick which suit they’d like to wear.

The main museum atrium opens up to a taller ceiling, able to accommodate several rockets about twenty feet high, but the Saturn V display outside somewhat desensitizes you to this. Around the open floor are several other displays, artifacts from the space race which all blend together to the untrained eye; shiny metal and sleek designs are the name of the game here. On one side of the room is a raised platform, a stage for special events, but none are happening at the moment.

It’s just past this room that the presence of youth-friendly areas ramps up as well. The Spark Lab, chaperoned by attendants, appears to be a sort of space-themed day care for the museum’s youngest visitors. The walls are adorned with colorful drawings, and shelves against the walls hold children’s books about cartoon astronauts and rocket ships. A board outside of the area advertises regular activities and classes to teach kids more about the science behind space travel.

Next to the Spark Lab is another room filled with more hands-on activities, presumably for kids a few years older. This room contains experiments demonstrating scientific properties which engineers have to take into account for space travel. These include a marble maze that illustrates the effects of air pressure, a series of clear blocks that reflect light in different ways, and even a giant air cannon which kids would undoubtedly have a lot of fun shooting each other with. At the moment, several children seemed more occupied with a giant scale, which teetered and shifted as four or five tried to cram their way onto it.

These exhibits for older children likely would have fascinated von Braun. In school, he largely paid attention to subjects regarding math and science in order to help him achieve his dreams. He excelled in these fields, and ended up graduating high school early as a result of his impressive performance.

Further down the hall, in a corridor to the next set of rooms, was a set of interactive rides. Piled into the corner, these constricting, gyrating contraptions promised to simulate the feelings of air travel and space adventure right here on Earth. I opted for Hypership, a rocket-shaped pod which offered an audiovisual experience that would supposedly simulate a journey through space. This journey proved to be particularly exciting; asteroids crash down on the surface of the moon as you and your crew drive a lunar rover over the deteriorating structures. It’s less educational and more Michael Bay, but I guess that’s what some audiences come for.

The number of visitors swells just past these rides. Although the halls were busy before, they’re almost crowded now; unusual for a weekday. The arrangement of the parties gives them away- groups of children, ranging from middle schoolers to early teens, each one following behind a college-aged leader. This is Space Camp, a summer program that gives kids around Huntsville and beyond the hands-on experience of being an astronaut. It also hopes to encourage them to get excited about the application of STEM subjects. Although much of this display is blocked to visitors, you are still welcome to look from a distance at what is perhaps the most impressive piece of this camp in the main museum. A series of cylindrical metal chambers stack on top of each other, creating a maze-like structure through what otherwise looks like a flat, open room. It’s not unlike the appearance of a playplace one would find at an old fast food restaurant, albeit less run-down and more futuristic. Inside the nearest chamber, two Space Camp students sit in slanted pilot’s seats while an instructor briefs them on their mission. This structure is in fact a replica of the International Space Station, built especially for youth to see what it’s really like to man the facility far beyond the atmosphere.

There is some significance in locating youth for this function, especially those who either live or are willing to travel to Huntsville. Within the city, and in fact just over the trees from where we are now, is the Redstone Arsenal. This military base serves as a hub for the development of rocket and missile technology, and is in fact where von Braun and his team began their work for the United States government. Finding potential engineers is no small task, and astronauts even less so. Considering the elite levels of scientific knowledge one must possess, in addition to extreme physical fitness and ability to remain calm under pressure, it’s no surprise that very few candidates may qualify for this role. By funneling as many children as possible through this camp, and so close to such a key testing facility, there is no doubt a desire to recruit some of the more promising ones for future endeavors.

The main museum ends just after the ISS replica for the most part; many of the remaining rooms are designated for Space Camp, but there is also a food court area known as the Mars Grill which serves typical American fare. However, there is an entire second building to explore, which must be accessed through an exterior courtyard.

Much of this area is under construction, but signs next to the fenced-off areas indicate that this is soon to be known as the Rocket Park.* Reddish-brown dirt enclosed by cement retaining walls surrounds a group of four rockets, similar in size to the one inside the building earlier. There’s also the much larger Saturn I rocket, a prototype of the striking Saturn V which dominates the skyline. The Rocket Park isn’t much to look at, but the current construction promises a closer look in the future.

It’s hard not to be distracted by the Saturn V looming ever closer, but before approaching it, one can find another set of interactive rides: the G-Force and Moon Shot simulators. Each one claims to exert around 3 Gs of force in different ways, simulating what astronauts feel on their way off the planet. A family with a young daughter loiter in front of G-Force, on the fence about actually taking the plunge. A group of children on Moon Shot scream and throw their hands up as the ride sends them surging back and forth. Next to Moon Shot is another set of smaller rockets along with a few military vehicles, including a submarine. Green metal and thick glass mark a change from the sleek white rockets that typically lie within the vicinity. It’s a subtle reminder of the government presence that seems to run deep within the space program as a whole.

And now you’re back at the Saturn V. Within the enclosing courtyard you can walk directly underneath the monolith of metal, its sheer scale almost dizzying to comprehend. The sleek black and white paint is only interrupted by patriotic imagery, American flags and “UNITED STATES” emblazoned against its sides. It’s a well-deserved tribute to an iconic human accomplishment, immortalized for all to see. Standing beneath the thrusters one might hear the echoes of a countdown in their head or imagine the heat exploding from above.

But in spite of all this, it’s not real. This Saturn V is just a model. The real one is inside the Davidson Center.

Next to the courtyard and up the stairs leads to the most impressive single room of the entire facility. The Davidson Center houses numerous artifacts from the space race, from physical acquisitions to historical footage and recordings. Walls upon walls of placards and displays outline many of the people and events that led to these offworld accomplishments. It’s a lot to take in, especially for the Space Camp students, who run to and fro amongst the artifacts. Many of them appear to be on a scavenger hunt; with papers in tow, they debate and squabble amongst themselves about where to find the next clue.

And above all of this, suspended from the ceiling of the facility, is the real Saturn V. Split into pieces, estranged from its former glory, it still commands the attention of those who set foot in the room. Its looming presence is a grand reminder of the results of a bygone era, one whose remnants are still chronicled right here. A walk around the room tells the full story; it goes something like this.

Arriving in Huntsville, von Braun and his team quickly got to work on the first satellite, Explorer I. The team accomplished this by way of a Jupiter-C launch vehicle, and this rocket was responsible for the satellite’s launch in 1958. This was all done without the use of computers; orbit calculations were done by hand, and the launch itself was manually operated. It was an impressive feat to be sure, and began the landslide towards one of the most significant moments in American history.

In the early 1960s, president John F. Kennedy famously declared that there would be a man on the moon by the end of the decade. This of course kicked off a race to the outer atmosphere, a titillating accomplishment that gripped more than just the American people. As tensions rose with the Soviet Union, each nation on the precipice of becoming the predominant superpower, there was more at play here than scientific advancement. The thought of reaching a new frontier became a source of pride.

Ideas were conceived, plans were drawn, and rockets were launched. One can only imagine spacecraft drifting across the cerulean, their plumes of smoke trailing past the ozone layer, that which was found on Earth leaving its home.

As technology advanced, so did the hope that soon there would be men in those same crafts. Hopefuls donned their flight suits. They were fascinated with the possibilities, likely awestruck from their very formative years like von Braun and the Space Camp children present even now. And together with the engineers of their crafts they began to work. Methodically, yet hastily, the spokes of the metaphorical gears turned as if they were about to burst off their axes.

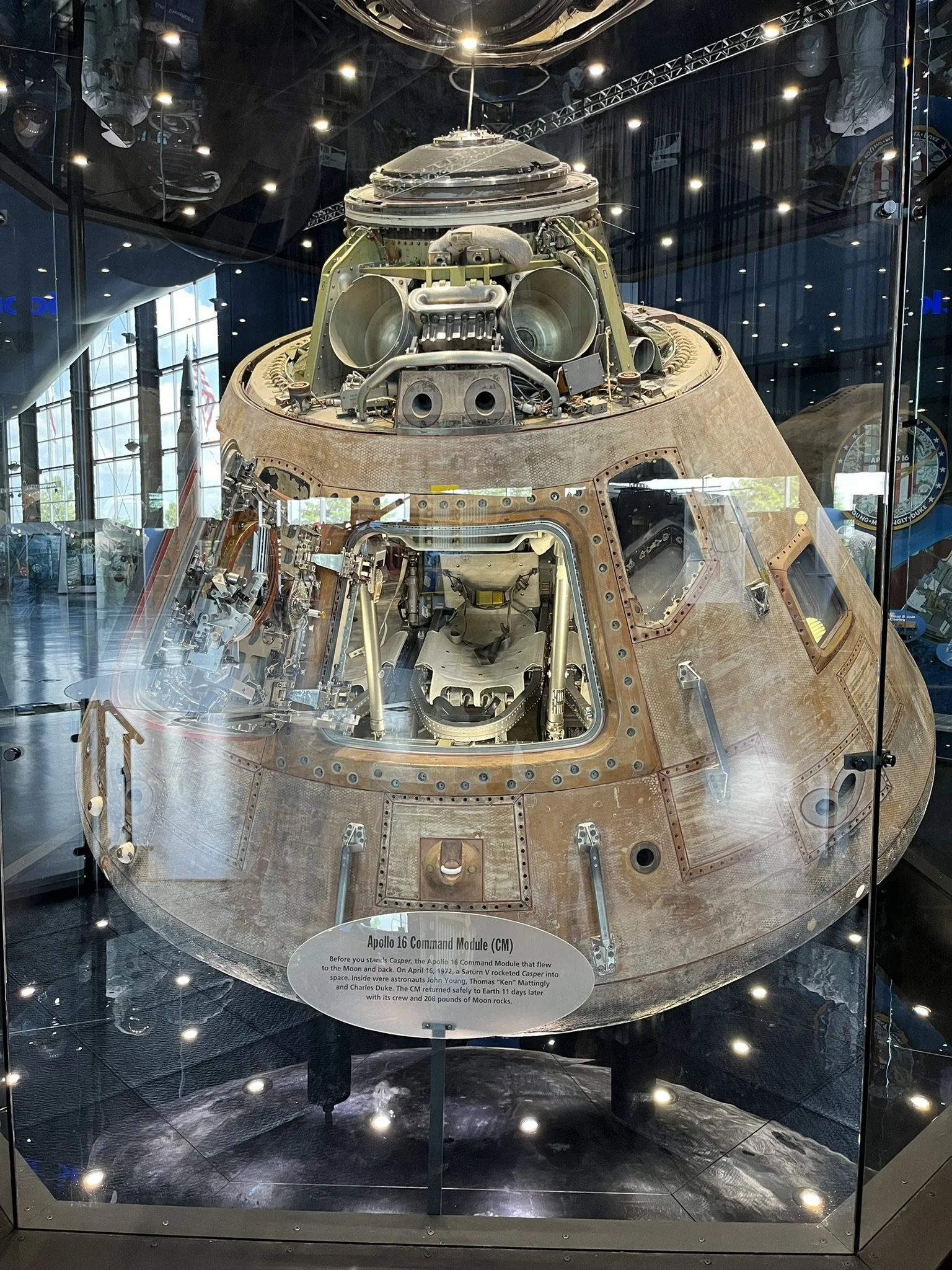

And now, the fruits of these labors lay here in this very hall. We of course know how this story ends; starting in 1969 the United States made not one, but several trips to the moon, and the very vessel which accomplished this feat now hangs from the ceiling. Some more of the artifacts which have touched that distant white orb are on display around the room. It’s striking how crude many of them look; little more than tubes of metal bolted together, with a dizzying amount of switches and dials inside their cockpits, the crafts seem to defy logic.

And yet, that very improbability is what so captivates those who wander through the museum even now. The idea that it came down to nearly chance, to infinitesimal values scrawled on pen and paper, to steel buckets shaped in precisely the right way so as to leave the very earth we stand on and return as a fiery comet whose contents remained intact. The fact that, after so many what-ifs and could-have-beens and worst-case-scenarios, those final missions ignored all of that to give us what is. That is the awe through which the museum works, the way it is so uncompromising in how it delivers something nearly incomprehensible.

Perhaps no place on the property does this better than the Planetarium theater. A dome-shaped video screen covers the ceiling, which is used for immersive shows that explore the outer reaches of space. The fan-favorite “Our Place in Space” is showing now, a virtual tour of the solar system narrated live by a chipper employee. As the camera careens further and further away from the Earth, he excitedly takes us through the boiling hot surface of the sun, the storms and craters of various moons and planets, and the cold, lonely outer recesses that no one has ever seen with their own eyes.

It’s a moving piece of multimedia, no doubt aided by the storytelling and enthusiasm of its narrator. The show ends by instilling a sense of wonder- the camera zooms outward, far beyond our solar system and nearby galaxies to present entire universes in a stunning display. The infinite celestial bodies occupy your entire field of vision thanks to how the Planetarium’s display wraps around you. The dizzying array presented here would leave anyone with questions, ones we may not have the answers to in our lifetimes. And yet, we will still ask them. Once again, it’s a child whose perception seems the best in this matter; they babble excitedly with their parents on the way out of the theater.

“There HAS to be life out there somewhere!”

The museum is at its best through the mind of a child, the passion of its community, the footage of von Braun’s team working around the clock to send someone far above. And you would be forgiven for leaving with that, the spectacle of the whole thing, as it’s in no way an exaggeration of the truth. Maybe that’s what I should have left with, the image of the Saturn V in the rearview telling all of the story I needed to know.

But it wasn’t.

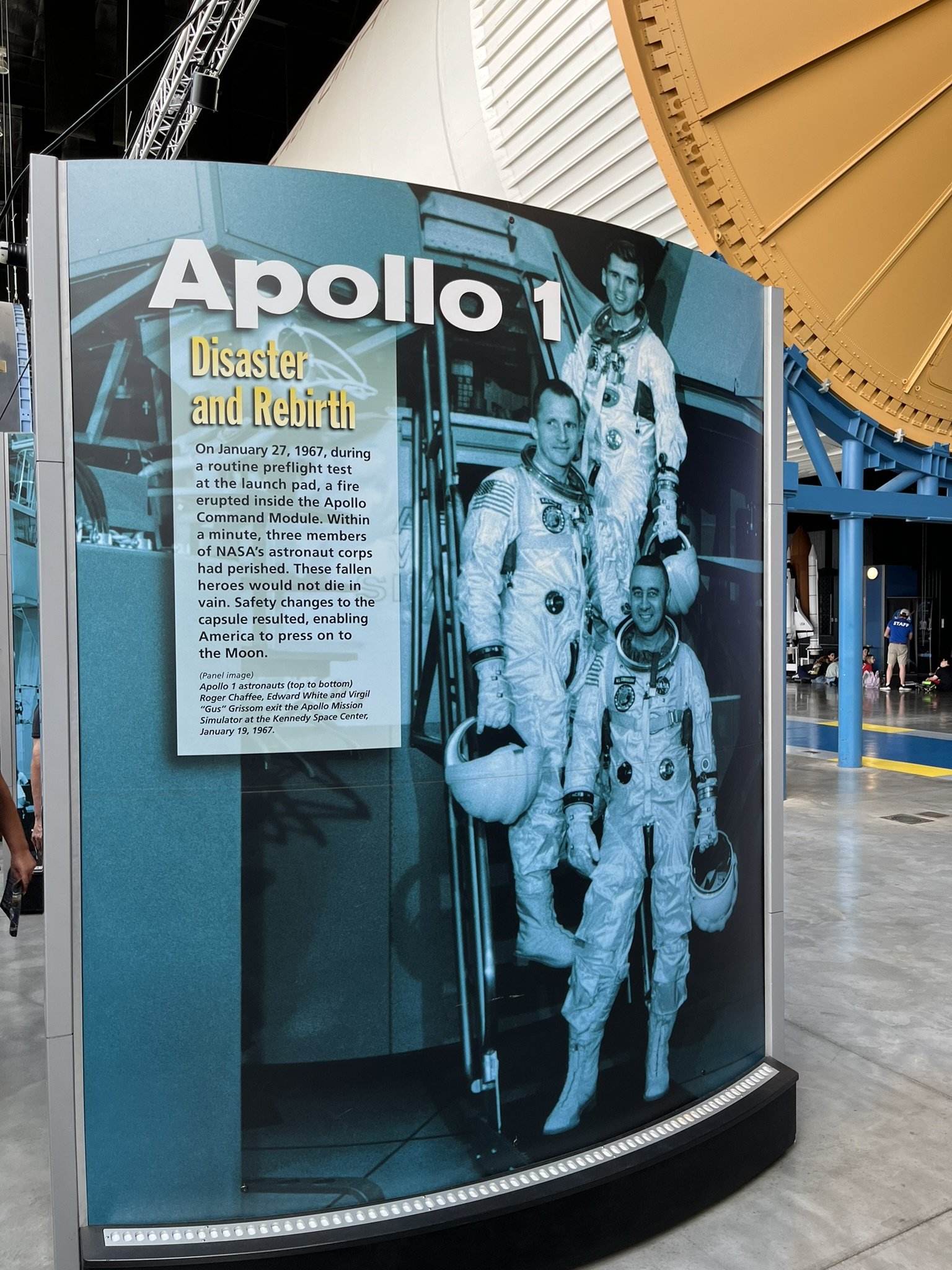

One sign in the Davidson Center details an incident two years before the first successful moon landing. Apollo 1, a rocket which underwent testing in 1967, was intended to be the first to put men on the moon. During one of these tests, in which three astronauts were onboard, disaster struck. A fire began, an unfortunate oversight in safety which ended up killing all three. Later on, fixes to the capsule enabled it to work properly.

It’s not much to go on, but the sign reveals little else. Most importantly, it reveals next to nothing about these safety changes and how long they would have taken. Were they major oversights, or simple fixes? And either way, how did engineers miss such a crucial step?

Like the children awestruck from the theater, I was asking questions now. The sterilized view of the incident offers few specifics and merely implores you to remember the sacrifice. But due to its position in the back half of the decade, was this project simply rushed? Was this grave error really an unforeseeable event, or did the ego of those in charge lead to the needs of the few outweighing those of the many?

Did those men really have to die?

We can’t say for certain, at least not with only this side of the story to go on. But the questions continue. Did the obsession with sending human life far from home lead to an attitude of the ends justifying the means? And what happens when that obsession leads you to lack ethical thought, to only be concerned with the goals in front of you rather than the collateral damage done along the way?

The answer can once again be found in the Davidson Center. This time it’s on a smaller sign, away from the enticing views of rockets, thrusters, bells and whistles. Almost like they didn’t want you to read it.

It tells of a scientist with humble beginnings as a member of a civilian rocketry organization. He was quickly eyed by his country’s government and enlisted as one of the chief engineers in their army. He was quick to design the V-2 rocket, a crucial piece of technology that would at first be tested and launched into the ocean. But the rocket soon became a weapon of war. Sixty thousand prisoners, forced into slave labor in the government’s concentration camps, were forced to manufacture the V-2 rockets. This country was Nazi Germany, and in 1944 they would launch the V-2 rockets towards London. The bloodshed of the innocent deep within the assembly plant was merely a prelude to the destruction they would hope to cause.

That scientist surrendered at the end of the war, testifying to having seen the camps himself. And by 1950, the United States government moved him to Huntsville, Alabama, where he would spearhead the team that put the Saturn V, and human life with it, on the moon.

His name was Wernher von Braun.

All figures and additional research courtesy of the U.S Space and Rocket Center, NASA.gov, and Al Jazeera.

*The Rocket Park opened about two weeks after my visit. It seems like it had been open before then, but the construction was in order to restore and rearrange it. You can read an article about it here.